WHOIS Privacy: How we got to this point, and how not to move backwards

In an era where online privacy is a key concern, a lot of people may wonder how WHOIS – the directory that holds the name, address, and other information for domain registrants – came to be in the first place, and where it’s going.

This blog post outlines how WHOIS began in the very early internet as a way to know what systems were available on a smaller network made up mostly of researchers, and how its current role, an entirely different one, should reflect the more public nature of the modern Internet.

Who’s on the Network?: The Origins of the Directory Problem

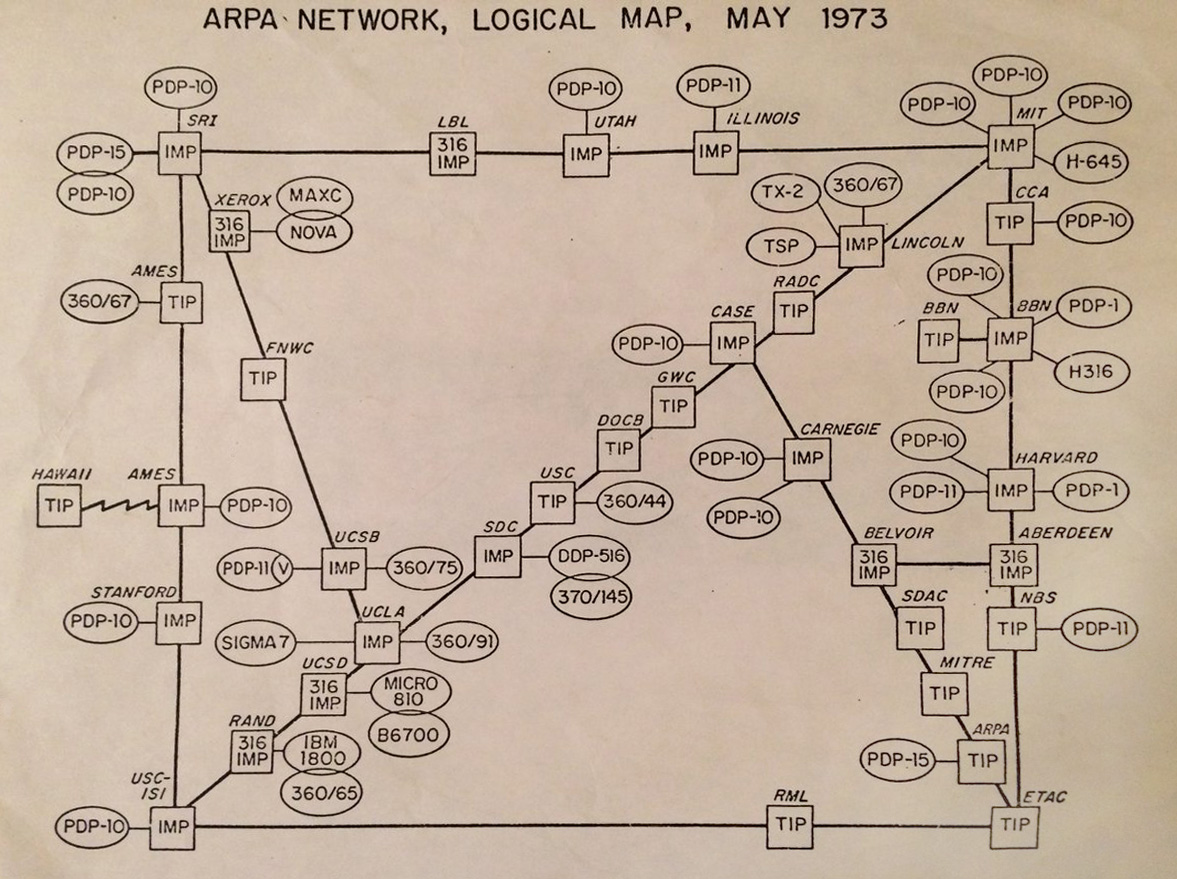

The Internet’s predecessor, the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network (ARPANET), was established in 1966 and was designed to share information between research centers in the United States. It had no distributed host name database – each network node maintained its own map of the network nodes as needed and assigned them names that were memorable to the users of the system.

In 1974, the Network Information Center took responsibility for administering the ARPANET’s central registry, which consisted of the names and numerical addresses of every machine on the ARPANET.

It might be surprising to know that the distributed directory service called the Domain Name System (DNS), which is now often referred to as the phone book for the Internet, actually traces its lineage from a physical book.

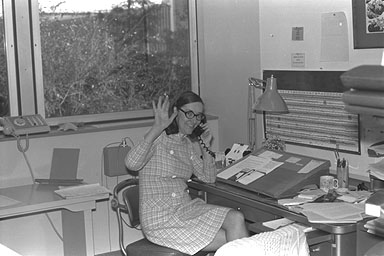

While working at NIC, Elizabeth Feinler created the Resource Handbook for ARPANET, a one-thousand page book containing information on nodes. Feinler was also the contact point for registering new hosts, which would be manually added to the directory. Since she and her colleagues had to manually update the physical network directory, it became larger and more unruly.

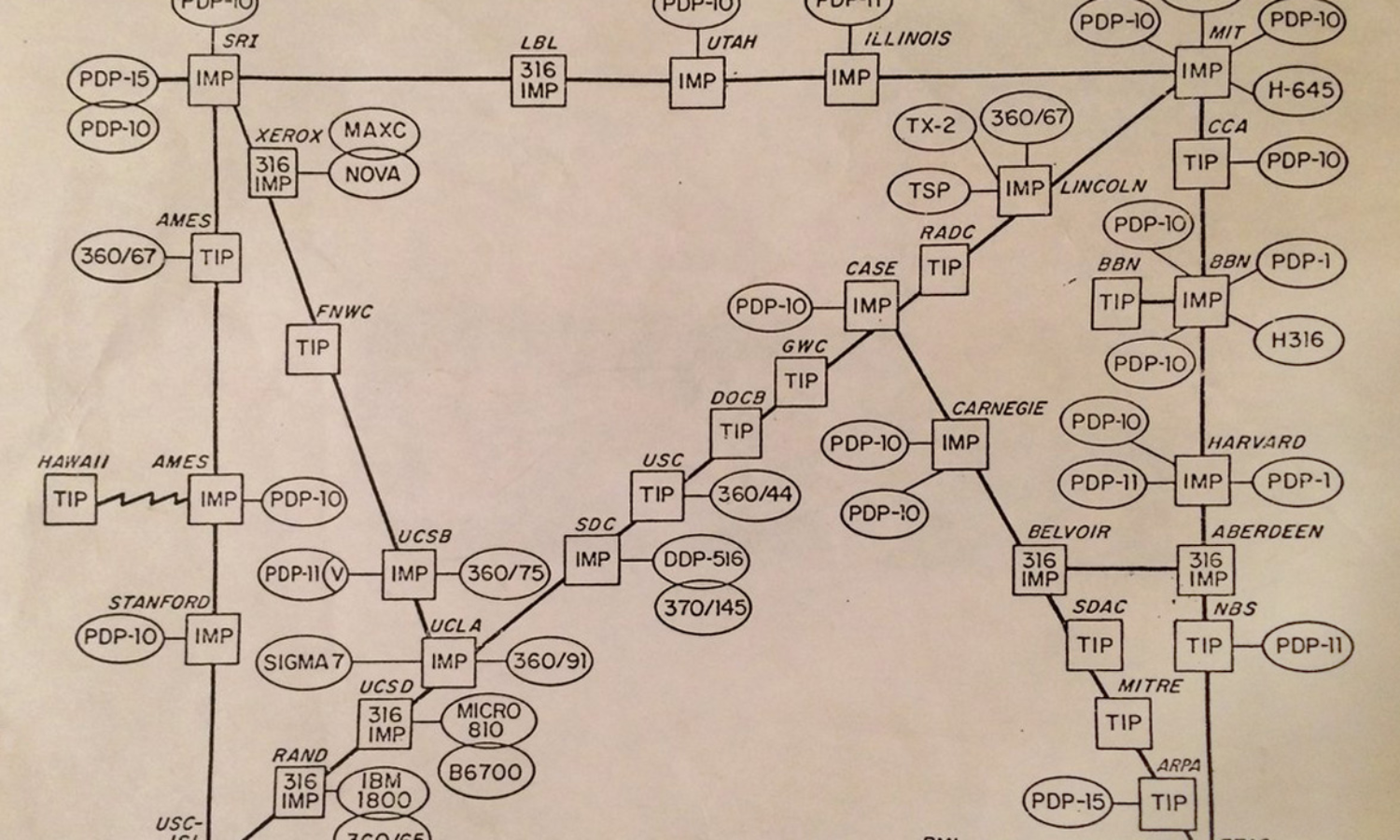

Before there was mapping of names to resource addresses, researchers would use diagrams to know what other systems they could connect to.

Elizabeth “Jake” Feinler, who managed the one-thousand page book listing all the devices that could be connected to on the ARPANET before more automated systems were developed.

The Resource Handbook ended up being replaced by HOSTS.TXT files that would contain the addresses and associated domain names in ASCII format for a given local area computer network. However, the maintenance of hosts files became a larger burden on system administrators as more networks and network nodes were being added.

There was also no automatic method for ensuring that all references to a given node in a network were using the same name, so more networked devices and sprawling lists of network’s identifiers meant more errors. To ensure there weren’t any mistakes in addressing, hosts would download the directory listing directly from the NIC. Network nodes typically had one address but could have many names.

This eventually led to DNS, which became core to how computer services and devices are located and identified on the Internet since the mid-1980’s. Unlike the Resource Handbook for ARPANET which identified where resources were located and who was involved, it essentially just defined how domain names would relate to specific online resources. It solved the problem of connecting computers with resources without needing to know who was associated with a domain.

But Who’s In Charge of a Domain?

In 1982, the Internet Engineering Task Force published a protocol for a directory service for ARPANET users – initially listing just the contact information that was requested of anyone transmitting data across the ARPANET.

This is essentially where the WHOIS traces its roots.

When that directory got too large, the NIC eventually deployed a new server called WHOIS to replace it. WHOIS basically performed the task of helping people find each other – which was previously accomplished by the Resource Handbook or even just phoning up NIC. The WHOIS protocol allowed for the querying of domains, people and other resources related to domain and number registrations, but only one centralized server was used for WHOIS queries in the 80’s.

A DNS Master File was stored on a domain name server as a text file (like HOSTS.TXT) that defines the DNS information for each DNS zone, defining where requests should be routed. This was fine when there were only a few hundred systems connected to the Internet in the 1980’s but the centralized and monolithic nature of hosts files eventually necessitated the creation of the distributed DNS.

A Distributed and Largely Public WHOIS

Over time, WHOIS began to serve the needs of different stakeholders such as domain name registrants, law enforcement agents, intellectual property and trademark owners, businesses and individual users. The millions of domain names registered every year require WHOIS data including name, address, email, phone number, and administrative and technical contacts. And because it was a fairly open database of personal information, it was also widely abused by scammers.

DNS had undergone significant modernization, but until 1998, when a non-profit called ICANN took over responsibility for it and set about modernizing it, the WHOIS service had changed very little since the original IETF standards were established.

Like DNS, WHOIS became a distributed set of databases. It was managed by independent “registrars” and “registries” accredited by ICANN and responsible for maintaining accurate records.

However, unlike the ARPANET, where the original researchers would have little concern about their name and location being revealed to other researchers on the network, normal people on the public internet might have legitimate concerns about having their identity revealed.

Since taking over WHOIS, ICANN has adopted various procedures around privacy, especially in regards to its compatibility with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (“GDPR”), leading to a temporary restriction on most personal data being published publicly, and tiered access to legitimate parties such as law enforcement under court order. ICANN is continuing to seek ways to refine a Registration Data Access Protocol (“RDAP”) for how registrars and registries operate address requests for information.

WHOIS Today

With its origins as a military-funded initiative for researchers, it makes sense that those connecting to the network would have to specify their name, address, phone number and other identifying information. But as the Internet grew and the concerns of domain identification and IP routing became further separated, the privacy of those owning domains became more fraught.

Luckily, a crucial separation between WHOIS and the routing of IP addresses emerged in the course of the Internet’s history. It was clear on the part of the stewards of the early Internet to have separate queries between DNS (for knowing the IP address associated with a domain), and WHOIS (who owns or operates a domain name).

Even so, WHOIS is still at the center of a long-running debate. Knowing who runs a domain is essential for the technical administration of the Internet, and should be available to authorities such as law enforcement to investigate criminal activities. But many are concerned that an open system like in the past is incompatible with today’s Internet and creates a potential for abuse.

Experts are working on the most appropriate updates to domain name registration information through ICANN’s Expedited Policy Development Process (EPDP). There’s a fine balance between user privacy and legitimate access by authorities. Policymakers may be frustrated with the timeframe required to get to the right solution. However, the EPDP is managing lots of complexities and working as fast as it can to do just that.

Finding a Privacy/Access Balance

It’s not an unlikely scenario that people could be misrepresenting themselves as owners of a domain because not everyone can access WHOIS records. However, authorities have the ability to make queries to the WHOIS database when there’s a demonstrated need.

In a recent interview, 1&1 IONOS Domain Services Director, Thomas Keller said legitimate access to domain data by formal request from parties like law enforcement did not result in a burdensome flood of requests. This is an indication that the balance between privacy and access is not elusive, and that we’re getting closer to a workable solution.

The next phase of WHOIS is being discussed in Phase Two of ICANN’s Expedited Policy Development Process (EPDP), which aims to develop a System for Standardized Access/Disclosure (SSAD) that assures registries and registrars are not in violation of GDPR; gives the users of WHOIS confidence that they can attain access to WHOIS information for pursuing their legitimate interests; and gives assurances to the wider Internet community that data protection is taken seriously.

While perhaps not as “quick” as some would want, the results of that process will ensure a solution that is workable, globally applicable, and in keeping with the overarching goal of maintaining a stable, secure, and resilient Internet.